Waste Streams

Tracing Romania's Tangled Trash

'Waste Streams – Tracing Romania's Tangled Trash' is an installation part of the exhibition 'Turn

Signals - Design is not a dashboard' at the FABER center, Timisoara (RO).

For years, the Romanian press has decried the nation’s portrayal as ‘the dump of Europe’. All types

of waste, both legal and illegal, find their way into Romania via boats and trucks, often

facilitated by corruption, economic interests, and political connections. However, the fate of this

waste within the country remains largely undisclosed. ‘Waste Streams — Tracing Romania’s Tangled

Trash’ investigated the waste management system by analysing statistics, policies, and legislations

within Romania and across Europe. Illustrated in the form of a waste sorting facility, one conveyor

belt is a visual representation of Europe’s waste production, export strategies, and associated

directives, shedding light on continental waste dynamics. Another conveyor belt focuses on Romania’s

waste infrastructure, and its health and environmental impacts. Drawing on data, news reports, and

local knowledge, the project converges diverse entry points into a single stream of information.

When viewed as a continuous flow of data involving imports, exports, and materials, the waste system

is acknowledged as a trade mechanism, wherein waste functions as a commodity.

The project has been realised in collaboration with

Versavia Ancusa, Computer Science lecturer at the Polytechnic of Timisoara

www.brightcityscapes.eu

Waste Streams. Installation view.

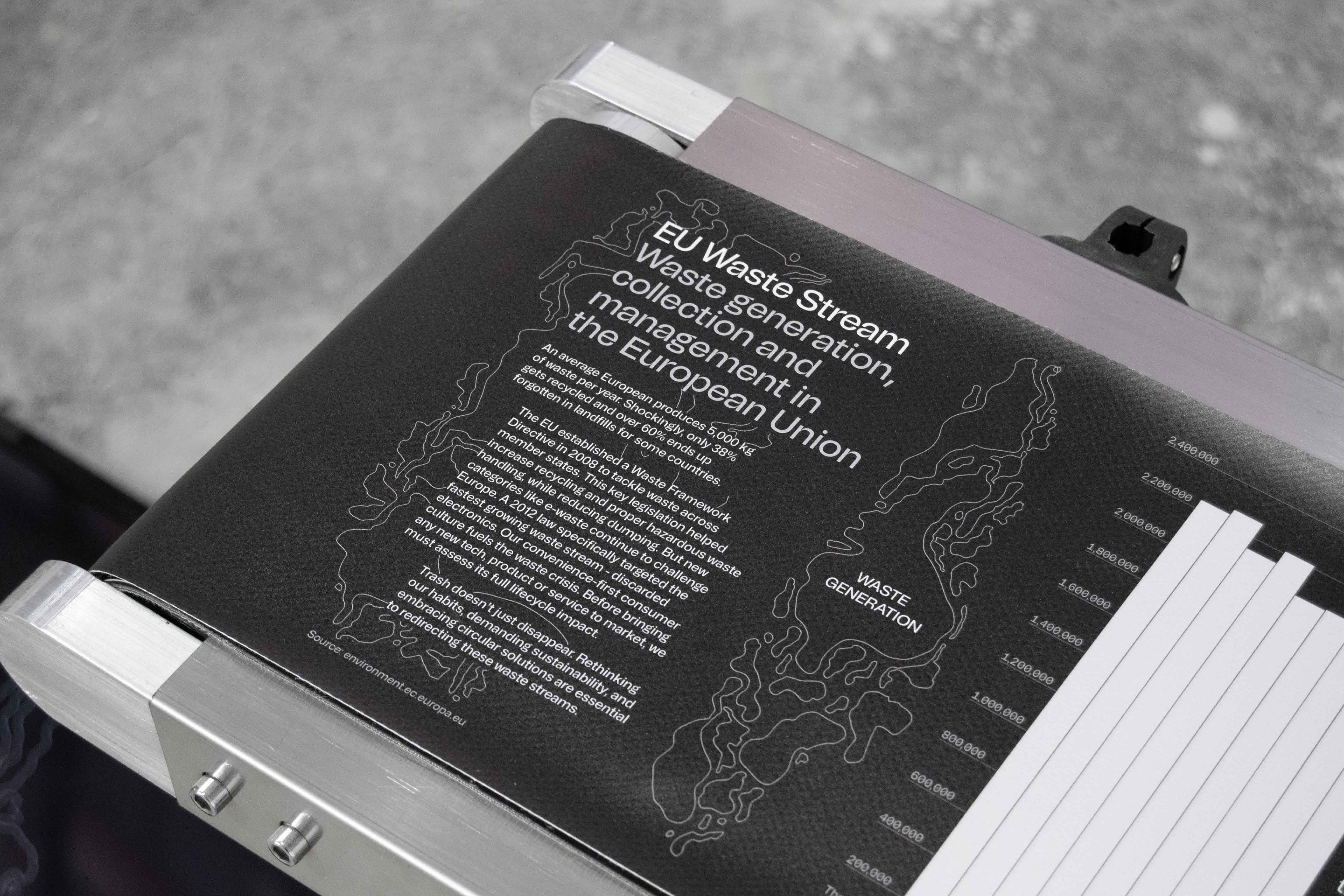

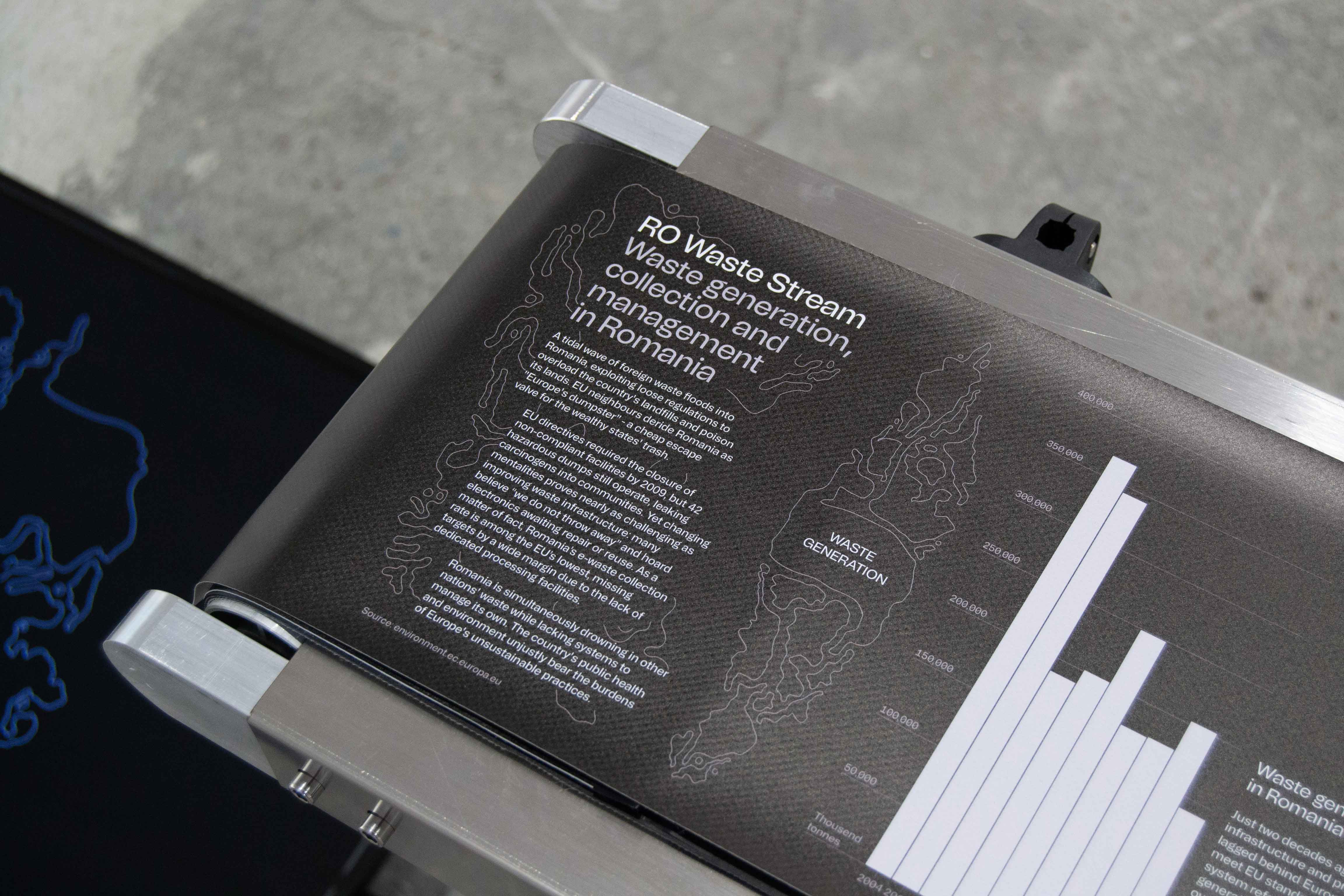

The Conveyor Belts

The installation features two conveyor belts showcasing information related to the waste management

system in Romania and the European Union. The two conveyors mirror each other, establishing a

symbolic comparison between the two geopolitical dimensions.

The belts, long 3 metres each, carry statistics, policies, and legislations within Romania and

across Europe up until 2020. The European belt showcases data extracted from Eurostat, which are

updated

every two years. The Romanian belt transports the same type of data, with additional information

obtained

from local news media and open source governmental data.

In terms of structure, each belt flow is divided in three chapters related to the waste management:

generation, treatment and export. Showcasing data between 2004 and 2020, the belts display an

introduction related to the current management and the total waste generated per year (both

displayed in tonnes and kg/capita). The data for the latest year (2020) are then analysed per

country and type of discarded material, as well as investigating the type of economic sector that

generates larger quantities of waste. Moving on to the chapter related to treatment, municipal waste

data are combined with e-waste figures, one of the fast-growing waste streams. Romania’s e-waste

collection rate is among the EU’s lowest, missing targets by a wide margin due to the lack of

dedicated processing facilities. The last chapter is then dedicated to the waste disposal and

export. After 2018, the year in which the European Parliament published the EU 2018 851 Waste

Framework Directive, we see a spark increase in the number of waste facilities, as well as a slow

decline in waste depots. However, outdated landfills remained Romania's primary waste disposal

method in 2020, even more so than five years prior, with cement kilns burning waste for energy. The

end of the belt displays data related to waste export by operation (treatment or recovery) and

material. The European belt lists the countries who exported to Romania in 2020 (we see Ukraine as

the first one with lots of wood waste), while its counterpart unveils the countries (EU and non-EU)

who Romania sent its waste to.

The endless rotation of the conveyor belts stand as a metaphor to the waste life-cycle. Always

thought of as the end-life of a product, waste is a commodity itself traded in a global market,

whose correct treatment is actually essential to the wellbeing of the living beings of our planet.

The Detection Cameras

Beneath the European conveyor, a screen displays a garbage segmentation dataset featuring 6

classification types: cardboard, glass, metal, paper, plastic and trash. It serves as a point of

reference for visitors, offering a clear contextualization of the research project. The years 2010

to 2020 brought a slight decline in the EU's waste generation (about 4.2% less). This short-lived

downward trend resulted from COVID-19 economic slowdowns between 2018-2020. Historically, waste

production has closely mirrored economic growth trends, but as the economic engine regains momentum,

it doesn’t seem likely that waste generation will diminish in the coming decade.

On the contrary, the monitor beneath the Romanian conveyor shows footage of illegal dumping

activities recorded in Timisoara and surroundings. These videos and images were captured by CCTV

cameras positioned close to trash containers, later published by local media outlets. Applying fines

and measures of “public shaming” does not stop the incorrect behaviour of some individuals. Many

Romanians cling to outdated notions like "the city will take care of it" or "everything can be

reused", and dump waste directly in the streets. A key challenge is shifting away from a

communist-era mindset, where waste collection was a centralised government service, where city

authorities collected all mixed waste directly from the citizens’ doorsteps. Today's capitalist

system requires more individual responsibility and effort.

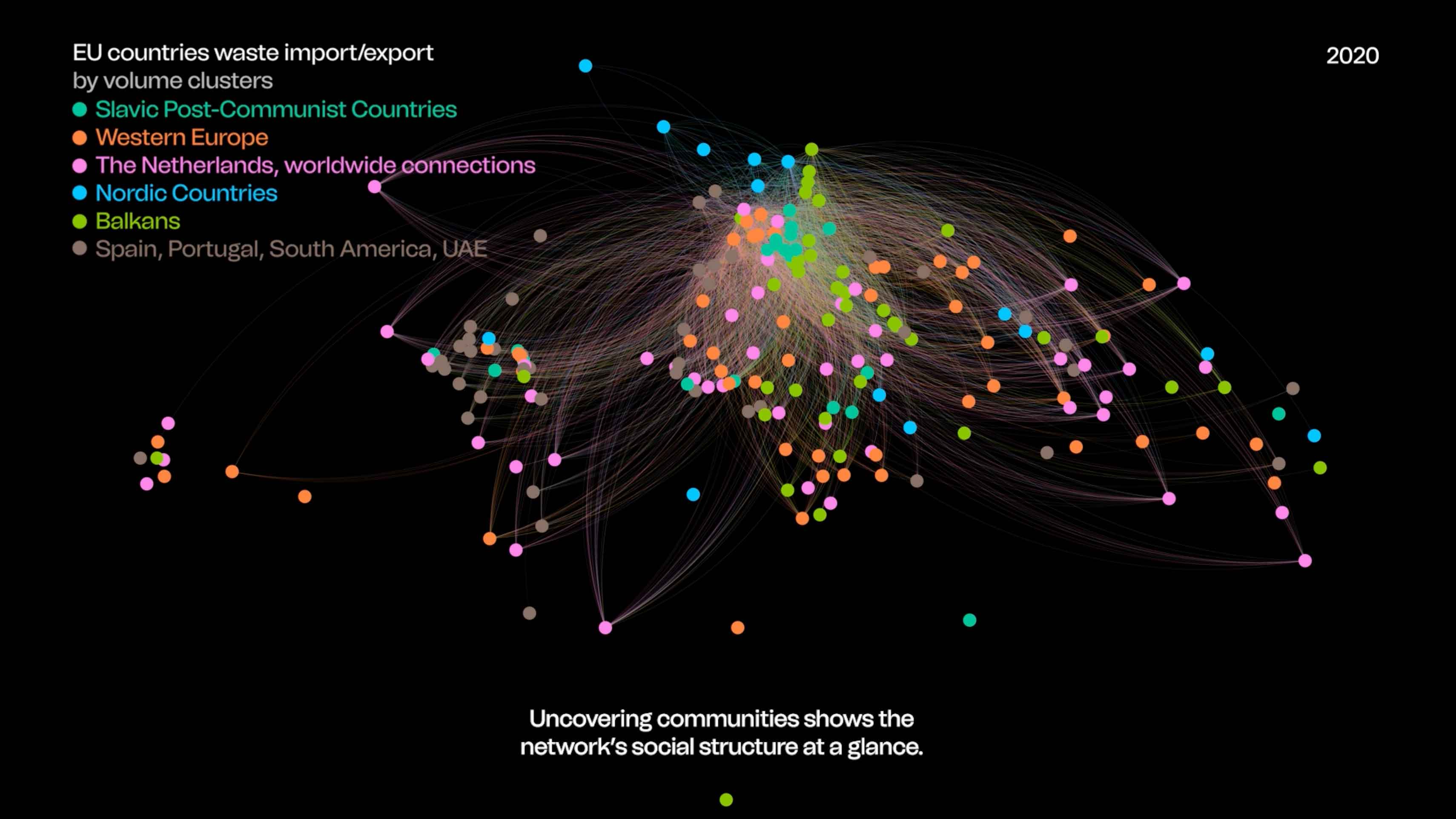

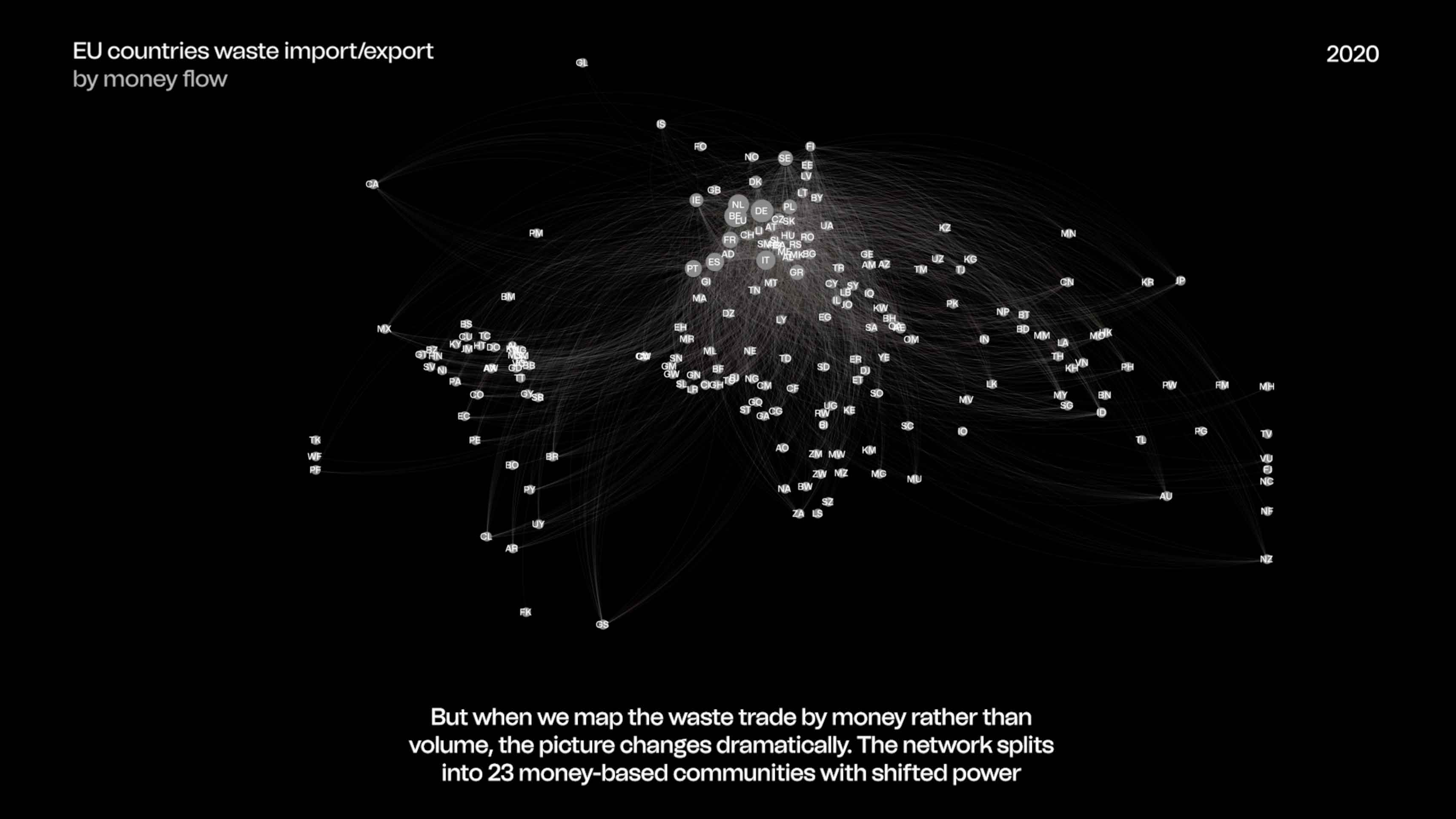

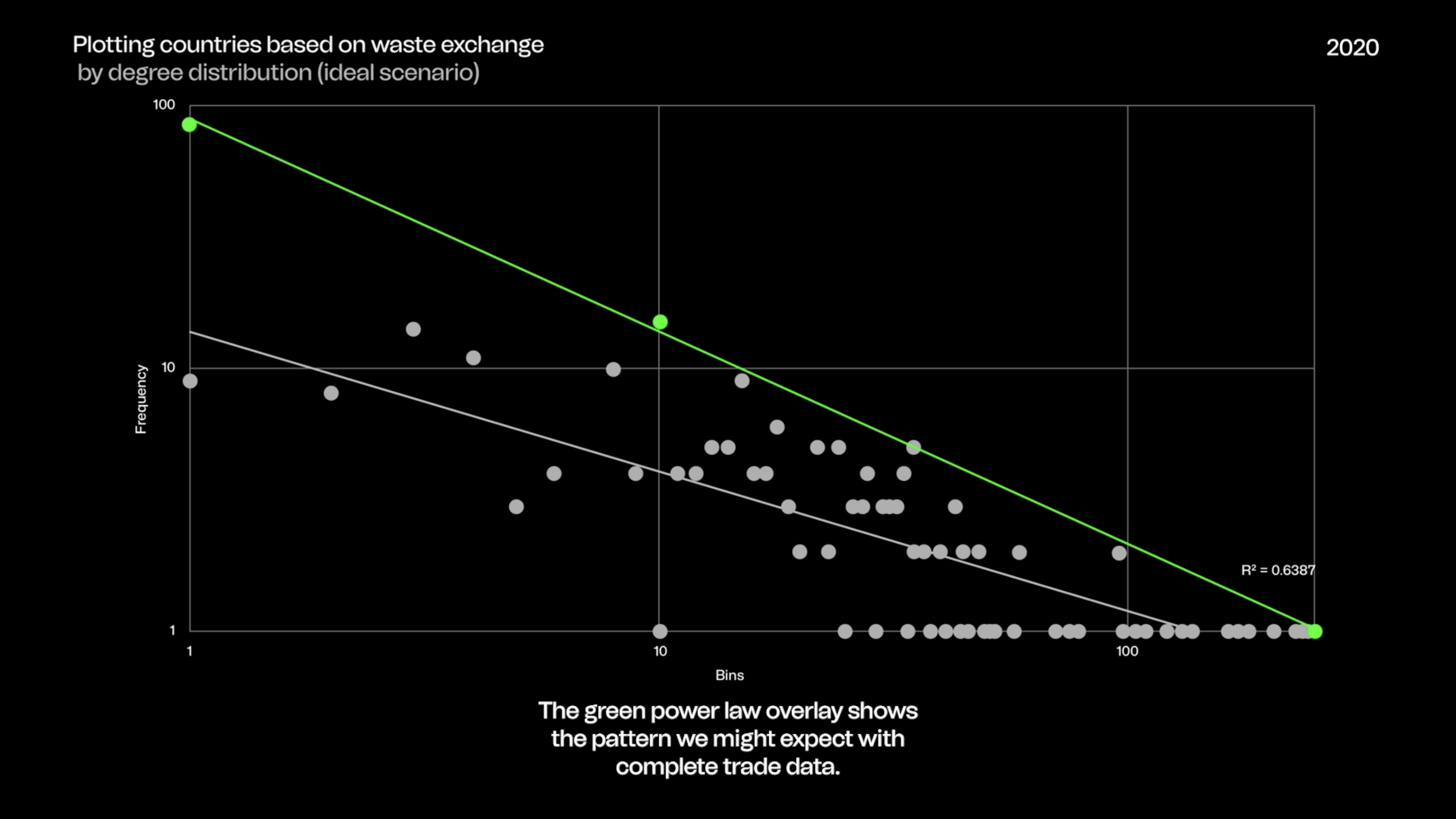

The Complex Network

At the beginning of the European conveyor, a large monitor displays the waste traded among EU (and

non-EU) state members. The complex network analysis, carried out by Versavia Ancusa, reveals

patterns and missing data of the cross-border waste systems.

Complex networks are graphs representing systems into dots and lines - nodes and the links between

them. When using a complex network to represent the global waste trade, hidden structural patterns

are revealed. Countries become dots, waste flows become lines: we can measure how central a node is

based on its connections, or we can spot clusters of nations closely linked by trash exports and

imports.

Eurostat’s datasets reveal a complex web of waste trade among 27 European countries and 218 global

partners from 2004-2021. The data spans for 18 years, over 200 nations, and waste exchanges tallying

both volume in tons and value in euros. Network maps can physically arrange countries based on their

coordinates, or mathematically position them by their waste trade links. Geographic layouts reveal

how waste flows across our real globe. But force-directed layouts let algorithms crunch trade data

and spatially group nations accordingly. Suddenly, layouts reflect realities of economics, not just

distance.

The Romanian Landfills

Finally, between the two conveyors is positioned a monitor displaying the recent evolution of 42

Romanian landfills. For years, the national press has decried the country as ‘the dump of Europe’.

All types of waste, both legal and illegal, find their way into Romania via boats and trucks, often

facilitated by corruption, economic interests, and political connections. Based on 2020 Eurostat

data, 319,608 tonnes of waste were legally imported in Romania: 66% was imported for recovery

procedure, while the remaining 34% has been processed for waste treatment. The data don’t say

whether it was burnt for energy production, incinerated or disposed of in landfills. Or even used as

material in cement factories. In 2021 alone, the Romanian border police identified 14,000 t of waste

illegally imported in the country.

Landfills are central to the waste crisis. EU directives required Romania to close non-compliant

facilities by 2009. In 2016, Romania’s recycling rate reported to Eurostat was 13%, while its

landfilling rate was 69%, one of the highest in Europe. The country received a warning report from

the European Commission in 2018 to stress preparation for re-use/recycling of municipal waste. This

led to an increment in the number of recycling facilities and an improvement on already existing

waste depots. Several non-compliant landfills were closed; however, their current condition is

unknown. Toxic leaks pollute air, soil, and water, causing respiratory illnesses, cancers, and birth

defects in nearby communities. Homes often border dumps, disproportionately affecting marginalised

groups like the Roma.

About the exhibition

Turn Signals—Design is not a Dashboard is an exhibition that explores the collaborative capacities

of design to transcend manufacturing conventions and to ignite a transformative trajectory for

Timisoara’s creative ecosystem. Demonstrating that design has a wider reach, the Turn Signals

exhibition features multidisciplinary design practitioners from Romania and beyond having

collaborated with local researchers on projects that bridge global and local perspectives, revealing

the city's products and resources, and connecting diverse places, people, and urgencies across

various scales. Anchored in a commissioned report that explores Timisoara’s historical and

contemporary economic and geographical context, Turn Signals employs different design media,

storytelling, and lexicons to dislocate hidden narratives and untapped potential within

Timisoara.

The exhibition is a component of the Bright Cityscapes programme, part of the Timișoara - European

Capital of Culture 2023 program, created by FABER and Politehnica University Timisoara.

www.brightcityscapes.eu

Participants

Théophile Blandet, Cinzia Bongino, Cristina Cochior, Jing He, Flora Lechner, Guillemette Legrand, Alina Lupu, Petre Mogoș and Laura Naum / Kajet Journal, Simone C Niquille /technoflesh Studio, Parasite 2.0, Santiago Reyes Villaveces.

Researchers

Versavia Ancușa, Ioan Both, Raul Ionel, Cristina-Sorina Stângaciu

Curator

Martina Muzi

Exhibition team

Bianca Schick, Federico Santarini, Alex Foradori

General coordination

Oana Simionescu, Loredana Gaiță

Graphic identity and platform

Kirsten Spruit

Production team

Lorena Brează, Sandro Damian, Nicușor Duma, Mihai Moldovan

Exhibition assistants

Karola Kalapati, Cristina Potra Mureșan, Lucian Stroia

Exhibition assistants

Communication: Ema Prisca, Diana Caducenco

Exhibition assistants

Editors: Nadine Botha, Cristina Potra Mureșan

Exhibition assistants

Research team: Norbert Petrovici, Vlad Alexe, Vlad Bejinariu, Agota Abran, Andrei Herța, Macrina Moldovan